After reading John Authers’ piece this morning, I was not really planning to write a note on yesterday’s FOMC meeting. I think he summed up the Fed’s actions very well and correctly analysed the market’s reactions. And I would say that indeed the mantra “Don’t fight the Fed” should be valid in general. But that holds true only if we understand what the Fed is trying to achieve. Here is a more nuanced view on the matter.

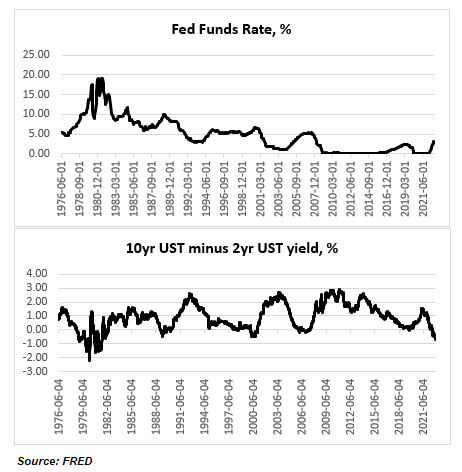

If the Fed had only raised the dot plot in the face of slowing down inflation since the last SEP (and obviously reiterated that there would be no cuts next year, etc.), I would have concluded that the Fed intends to keep hiking, regardless, bound not to repeat the ‘mistakes’ of the late 1970s. Don’t fight the Fed in this case would have been the right strategy.

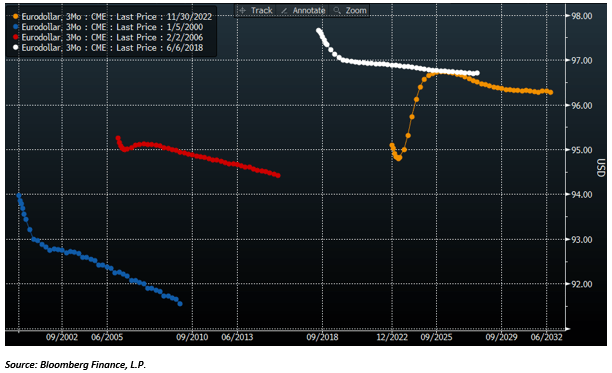

However, raising the dot plot in the face of slowing inflation but also alluding to a smaller hike than priced in the next FOMC meeting (see Authers’ note above) introduces a decent amount of confusion as to exactly what the Fed’s intentions are. It could be that most Fed members had made up their mind about the dot plot before the surprise slowdown in inflation this week and didn’t bother/didn’t have the time to adjust their view thereafter. The intention for a smaller hike next allows Fed officials to change their mind. So, in this case the market’s reaction (nothing really changed post the meeting[i]) might be justified.

It could also be that Fed officials took the lower-than-expected CPI in stride and concluded that it alone does not warrant a change in view. That also signifies that during the previous SEP, the Fed made a mistake in its projections of the terminal Fed rate (it should have been ‘much’ higher). Does that mean “Don’t fight the Fed” holds in this instance? It appears so, but then again, if the Fed made a mistake in the past and was quick to acknowledge it, then it is also possible that the Fed is again making a mistake. The market’s reaction is thus dubious, neither ‘wrong’, nor ‘right’.

The final possibility is that the Fed has literally and figuratively lost the plot (pun intended) and is planning to stay hawkish (not necessarily continue to hike, but certainly not cut) until the inflation rate crosses back below 2%, regardless of what happens to the economy. It must be clear that in this case “Don’t fight the Fed” firmly holds.

I have no idea what most of the other FOMC members’ intentions are but listening to Fed Chairman Powell’s press conference, I am pretty sure what his are: I think he is firmly in the last camp above. Here is why.

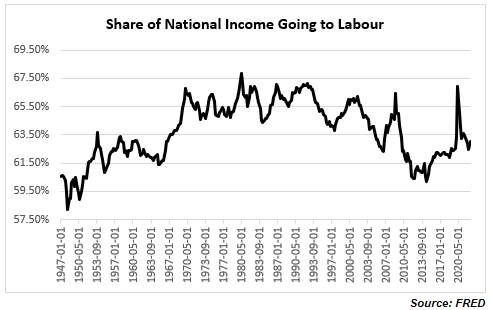

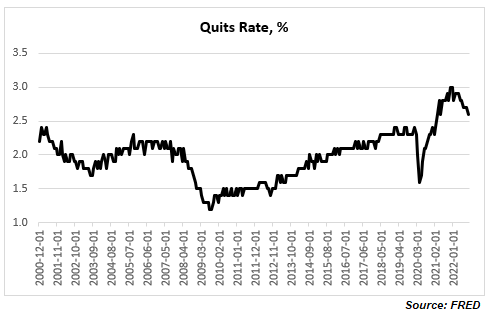

In his opening statement, Powell made several references to the fact that the “labor market remains extremely tight with the unemployment rate near a 50-year low, job vacancies still very high, and wage growth elevated”. In the Q&A session, similar, “I’ve made it clear that right now, the labor market is very, very strong. You’re near a 50 year low: you’re at or above maximum unemployment in 50 years.” I’ve written on this before, i.e., why not only I disagree that the labour market is so tight but that it is actually slowing down.

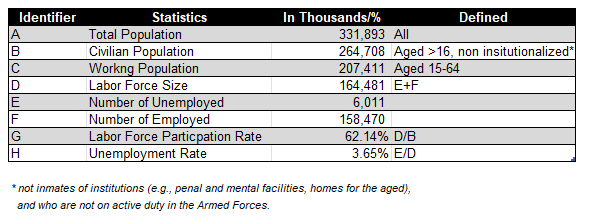

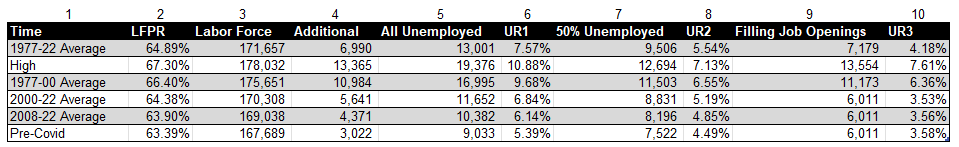

However here is some additional color, which shows that it is not that straightforward, and we have to give at least some credit to Chairman Powell. So, when it comes to the US labor market statistics the table below provides the basics. Bear these in mind as we go along.

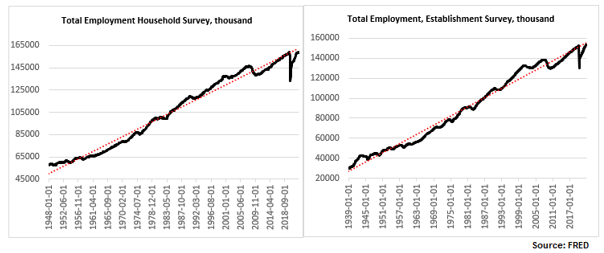

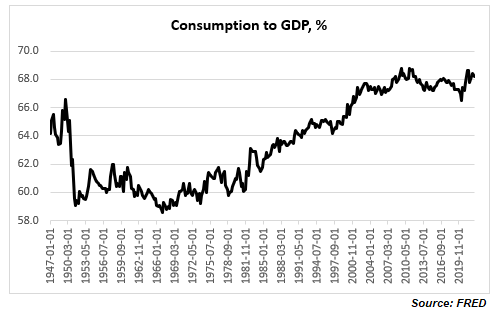

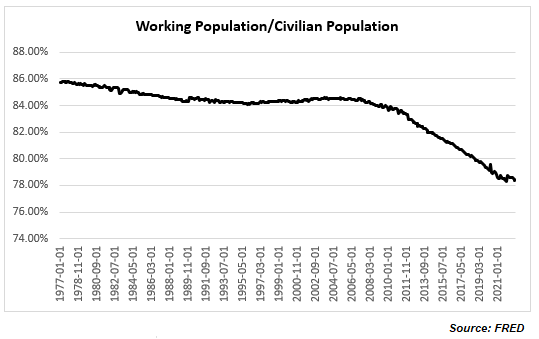

Strictly speaking, Chairman Powell is right that “the labor market continues to be out of balance, with demand substantially exceeding the supply of available workers” (in his opening statement; he goes in more detail on this in the Q&A session particularly in a question from Market Watch). Look at the ratio of Working Population to Civilian Population which is at nearly 50yr low

And within the Working Population the actual Labor Force Size only managed to get just above its pre-Covid level this August and has started to decline again since then, so that the ratio between the two is still below the pre-Covid level (and as a matter of fact still below the high reached at the onset of the 2000 recession).

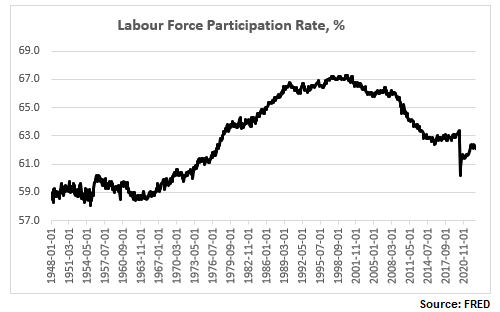

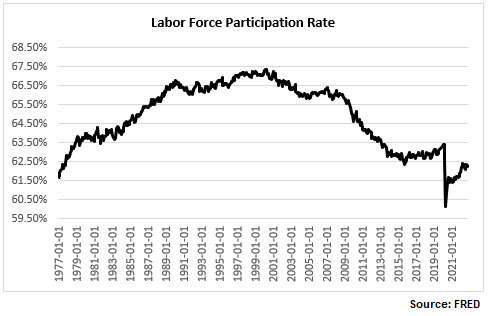

And here is the now more familiar labor force participation rate (LFPR), still way below the pre-Covid high and substantially below the pre-2000 recession high.

So, when Powell refers to the “labor market is 3.5m people smaller than it should have been based on pre-pandemic levels” this is what he has in mind: strictly speaking, if we adjust the LFPR to its pre-Covid high, the labor force would have been about 3.021m people more. But that is on the supply side, and we are going to go through this more later on.

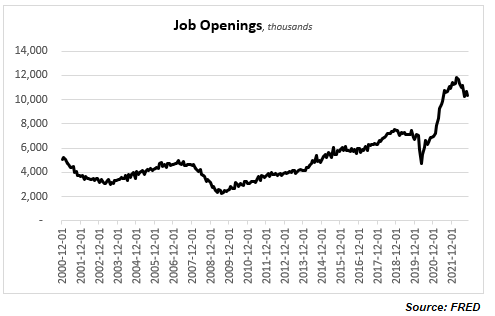

But let’s look at the demand side as well. As per Powell, again in the answer to the journalist from Market Watch, “you can look at vacancies”. Here they are.

Powell is right to an extent: there are still more that 10m job openings. This is down from nearly 12m from the highs in March, and job openings are never zero, but even the current number puts job openings at about 5.8m additional vacancies over the pre-Covid average.

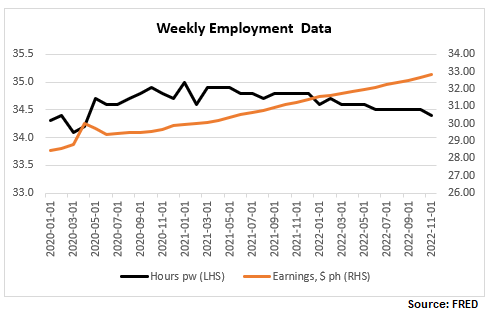

So, the question really is to square the demand and the supply side of labor. Obviously, it is not that straightforward. It is normal to have people unemployed at the same time as vacancies unfilled, but the state of the labor market post Covid is more unusual, also because the unfilled vacancies are not pushing real wages up. Which is why some people have suggested that rather than a wage issue it is really a skill mismatch issue (plenty of studies done on this post the 2008 recession), or indeed Covid-related issue (even Powell referred to this as a cause in his Q&A).

Chairman Powell lamented yesterday that the LFPR is not going up, “contrary to what we thought”. But if it does go up, does it mean the headline statistics will indicate the labor market is tightening or loosening? I ran some hypothetical numbers regarding this below.

The second column in the table above indicates a hypothetical LFPR per the time period in column one. The third column is the actual labor force as a result (in thousands). The fourth column indicates the additional people coming into the labor market. The fifth column indicates the number of unemployed if all these additional people entered the labor force; the sixth column is the resulting unemployment rate. The seventh column shows the number of unemployed if 50% of the additional labor force actually found jobs; the eight column is the resulting unemployment rate. Finally, the ninth column shows the number of unemployed if all the additional labor force fills the job openings (see Chart above) over and above the average pre-Covid; the tenth column shows the resulting unemployment rate.

There are myriad such scenarios. In the example above, using averages and simple assumptions about additional employment vs unemployment, the unemployment rate is higher than the current one in all but the last three examples (column 10 – the last three entries). Bottom line is that the drop in the labor force participation rate makes relative comparisons about how tight the labor market is (i.e., looking only at the unemployment rate) pretty irrelevant.

It also makes all of the above analysis almost useless (or at best very theoretical) as far as investing is concerned. It really does not matter at the end what the ‘real’ employment situation is. Powell was very clear yesterday. “The largest amount of pain” would not come from people losing their jobs. “The worst pain would come from a failure to raise rates high enough and from us allowing inflation to become entrenched in the economy; the ultimate cost of getting it out of the economy would be very high in terms of unemployment, meaning very high unemployment for extended periods of time.”

That’s it. Inflation is all that matters. And if there was any hint at all that the Fed might increase its 2% inflation target, Powell was very adamant that it is not happening: “…changing our inflation goal is just something we’re not, we’re not thinking about. It’s not something we’re not going to think about it. We have a 2% inflation goal and we’ll use our tools to get inflation back to 2%. I think this isn’t the time to be thinking about that. I mean there may be a longer run project at some point. But that is not where we are at all at the committee, we’re not considering that. We’re not going to consider that under any circumstances we’re gonna we’re gonna keep our inflation target at 2%.”

This turned out to be a long note just to conclude that indeed, it is pointless to fight the Fed, assuming that Powell’s view is shared by the majority of Fed voters, or if not, that the majority would still fall under the guidance of the Chairman. However, leaving the possibility of only 25bps hike at the next FOMC meeting is perhaps a sign that there may be some disagreement at the Fed.

[i] During New York hours; the market has subsequently weakened during the European morning session.