‘Banning’ buybacks won’t help, say the experts! Of course, it would, but you have to do it within the context of reversing shareholder profit maximization.

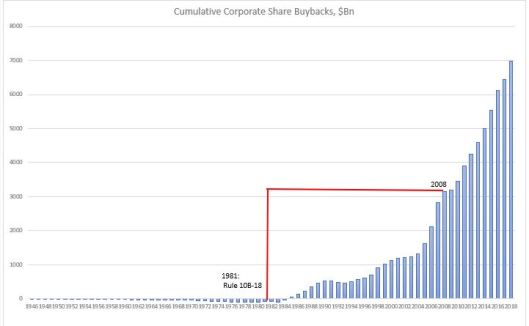

The SEC Rule 10b-18, which provided a ‘safe haven’ for share buybacks (they were never actually illegal), came into being in 1982. But the fertile ground of financialization and shareholder primacy thinking was already laid down in 1979. The theoretical ideas actually started fermenting even before, in 1932, with A. Berle’s and G. Means’ “The Modern Corporation and Private Property”, and culminated with “The Friedman doctrine” in 1970.

There is a huge misunderstanding about share buybacks before and after SEC Rule 10b-18. Buybacks were not ‘illegal’ before 1982, but the courts would generally be harsher on the interpretation of why they were conducted. Therefore, few companies attempted them. And it had all to do with the thinking behind ‘what is the purpose of a corporation’. For example, in the period 1900-1979, “courts were virtually silent on the idea of profit maximization”*. However, starting in the mid-1980s, this changed dramatically.

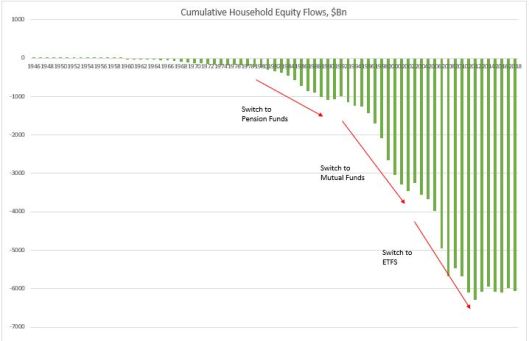

What followed was a spur of financialization, share buybacks and frantic M&A activity, all in line with finding innovative ways to reward shareholders. This resulted in a drastic decline in publicly traded US companies and the ‘oligopolization’ of US economy. Something which was undeniably good for shareholders became also questionably not so good for the economy and for everyone else, who is not a shareholder. In fact, the percentage of Americans who own shares in publicly traded companies has also declined in the process.

Shareholders primacy is often described as a ‘doctrine’, i.e. a mere belief system, when, in fact, it is much more than that. It is a “judge-made law” which means that “these varying levels of judicial embrace across many jurisdictions and over a long period have legal and jurisprudential significance.”*

This is important to understand. SEC Rule 10b-18 is not a law, but a rule within a complex maze of judicial proceedings and interpretations. Reversing that rule in isolation will do no good indeed as CEOs will find other way to return money to shareholders and they will be not only justified to do this by the corporate incentive system but also protected by the system of law. But reversing this rule in the context of questioning the point of shareholder profit maximization is a must.

And, just like in the early 1980s when it was first introduced, the fertile ground of reversing it has already been laid out a few years ago by the writings of people like William Lazonick, Lynn Stout and a few others. Having put this issue on Washington’s agenda, we may be indeed reaching an inflection point at next year’s presidential election.

*”A Legal Theory of Shareholder Primacy”, Robert J. Rhee