Tags

Following up on the ‘easy’ question of what to expect the effect of the Corona Virus will be in the long term, here is trying to answer the more difficult question what will happen to the markets in the short-to-medium term.

Coming up from the fact that this was the steepest 6-day stock market decline of this magnitude ever (and notwithstanding that this was preceded by a quite unprecedented market rise), there are two options for what is likely to happen next week:

- During the weekend, the number of Corona Virus (CV) cases in the West shoots up (situation starts to deteriorate rapidly) which causes central banks (CB) to react (as per ECB, Fed comments on Friday) -> markets bounce.

- CV news over the weekend is calm, which further reinforces the narrative of ‘this too shall pass’: It took China a month or so, but now it is recovering -> markets rally.

While it is probably obvious that one should sell into the bounce under Option 1, I would argue that one should sell also under Option 2 because the policy response, we have seen so far from authorities in the West, and especially in the US, is largely inferior to that in China in terms of testing, quarantining and treating CV patients. So, either the situation in the US will take much longer than China to improve with obviously bigger economic and, probably more importantly, political consequences, or to get out of hand with devastating consequences.

It will take longer for investors to see how hollow the narrative under Option 2 is than how desperately inadequate the CB action under Option 1 is. Therefore, markets will stay bid for longer under Option 2.

The first caveat is that if under Option 1 CBs do nothing, markets may continue to sell off next week but I don’t think the price action will be anything that bad as this week as the narrative under Option 2 is developing independently.

The second caveat is that I will start to believe the Option 2 narrative as well but only if the US starts testing, quarantining, treating people in earnest. However, the window of opportunity for that is narrowing rapidly.

What’s the medium-term game plan?

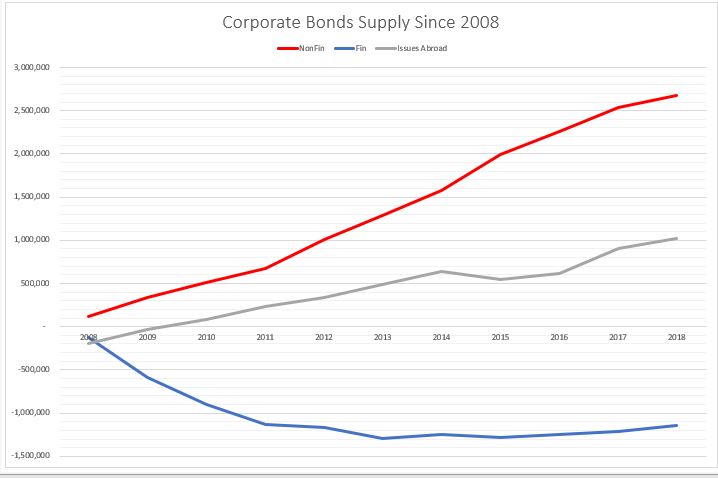

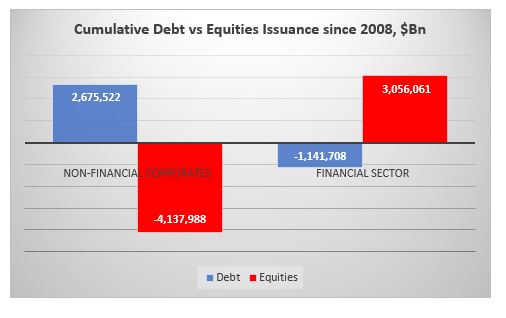

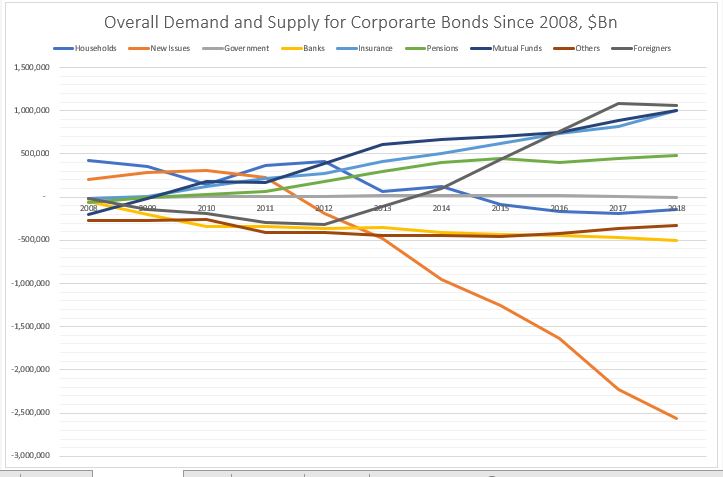

I am coming from the point of view that economically we are about to experience primarily a ‘permanent-ish’ supply shock, and, only secondary, a temporary demand shock. From a market point of view, I believe this is largely an equity worry first, and, perhaps, a credit worry second.

Even if we Option 2 above plays out and the whole world recovers from CV within the next month, this virus scare would only reinforce the ongoing trend of deglobalization which started probably with Brexit and then Trump. The US-China trade war already got the ball rolling on companies starting to rethink their China operations. The shifting of global supply chains now will accelerate. But that takes time, there isn’t simply an ON/OFF switch which can be simply flicked. What this means is that global supply chains will stay clogged for a lot longer while that shift is being executed.

It’s been quite some since the global economy experienced a supply shock of such magnitude. Perhaps the 1970s oil crises, but they were temporary: the 1973 oil embargo also lasted about 6 months but the world was much less global back then. If it wasn’t for the reckless Fed response to the second oil crisis in 1979 on the back of the Iranian revolution (Volcker’s disastrous monetary experiment), there would have been perhaps less damage to economic growth. Indeed, while CBs can claim to know how to unclog monetary transmission lines, they do not have the tools to deal with supply shocks: all the Fed did in the early 1980s, when it allowed rates to rise to almost 20%, was kill demand.

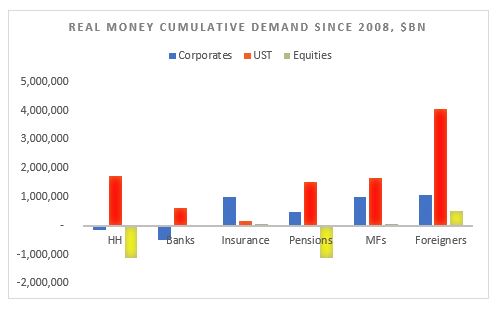

CBs have learnt those lessons and are unlikely to repeat them. In fact, as discussed above, their reaction function is now the polar opposite. This is good news as it assures that demand does not crater, however, it sadly does not mean that it allows it to grow. That is why I think we could get the temporary demand pullback. But that holds mostly for the US, and perhaps UK, where more orthodox economic thinking and rigid political structures still prevail.

In Asia, and to a certain extent in Europe, I suspect the CV crisis to finally usher in some unorthodox fiscal policy in supporting directly households’ purchasing power in the form of government monetary handouts. We have already seen that in Hong Kong and Singapore. Though temporary at the moment, not really qualifying as helicopter money, I would not be surprised if they become more permanent if the situation requires (and to eventually morph into UBI). I fully expect China to follow that same path.

In Europe, such direct fiscal policy action is less likely but I would not be surprised if the ECB comes up with an equivalent plan under its own monetary policy rules using tiered negative rates and the banking system as the transmission mechanism – a kind of stealth fiscal transfer to EU households similar in spirit to Target2 which is the equivalent for EU governments (Eric Lonergan has done some excellent work on this idea).

That is where my belief that, at worst, we experience only a temporary demand drop globally, comes from, although a much more ‘permanent’ in US than anywhere else. If that indeed plays out like that, one is supposed to stay underweight US equities against RoW equities – but especially against China – basically a reversal of the decades long trend we have had until now. Also, a general equity underweight vs commodities. Within the commodities sector, I would focus on longs in WTI (shale and Middle East disruptions) and softs (food essentials, looming crop failures across Central Asia, Middle East and Africa on the back of the looming locust invasion).

Finally, on the FX side, stay underweight the USD against the EUR on narrowing rate differentials and against commodity currencies as per above.

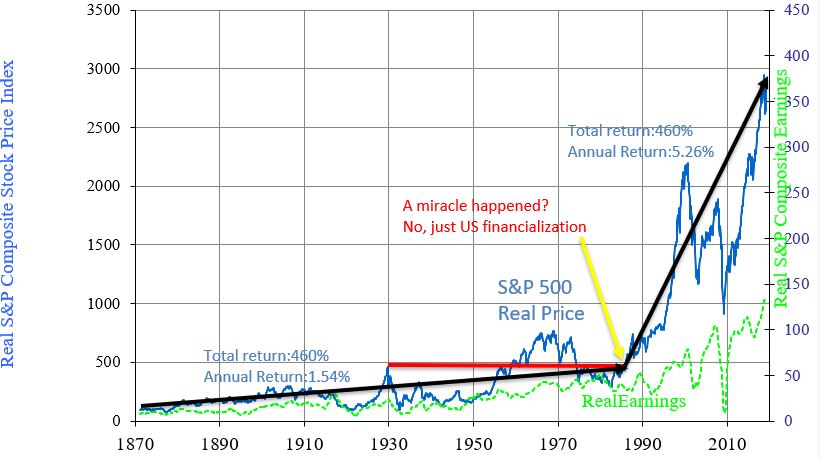

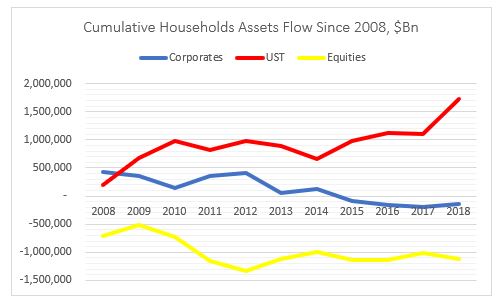

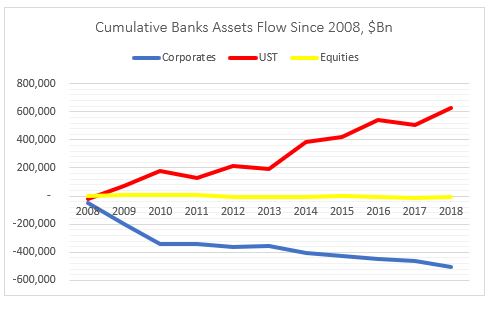

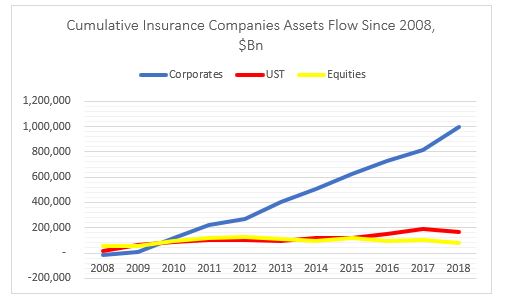

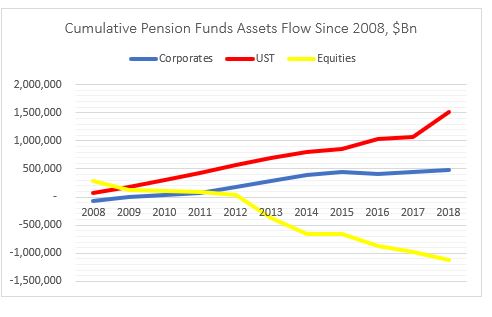

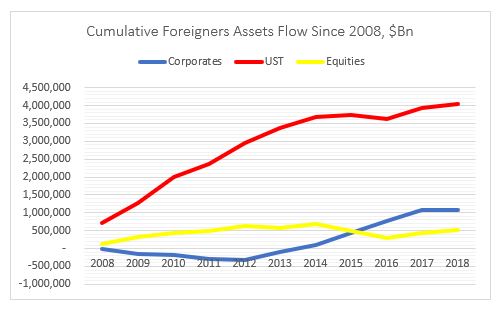

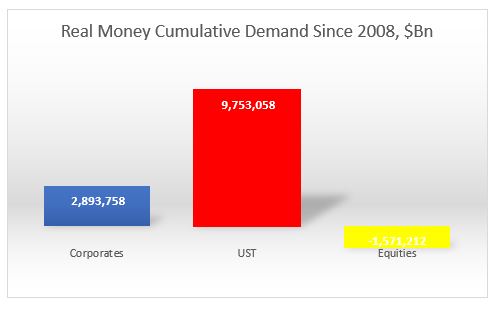

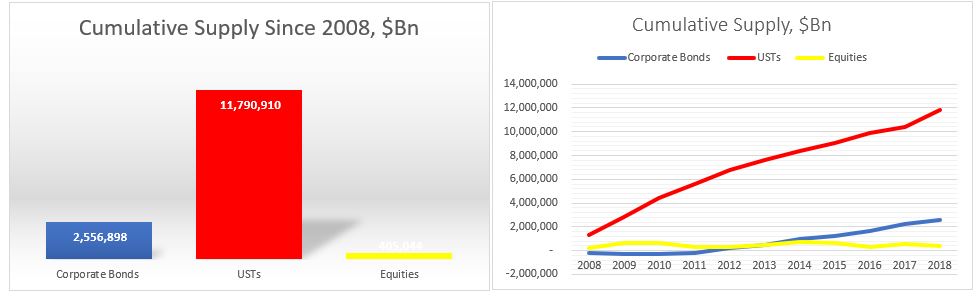

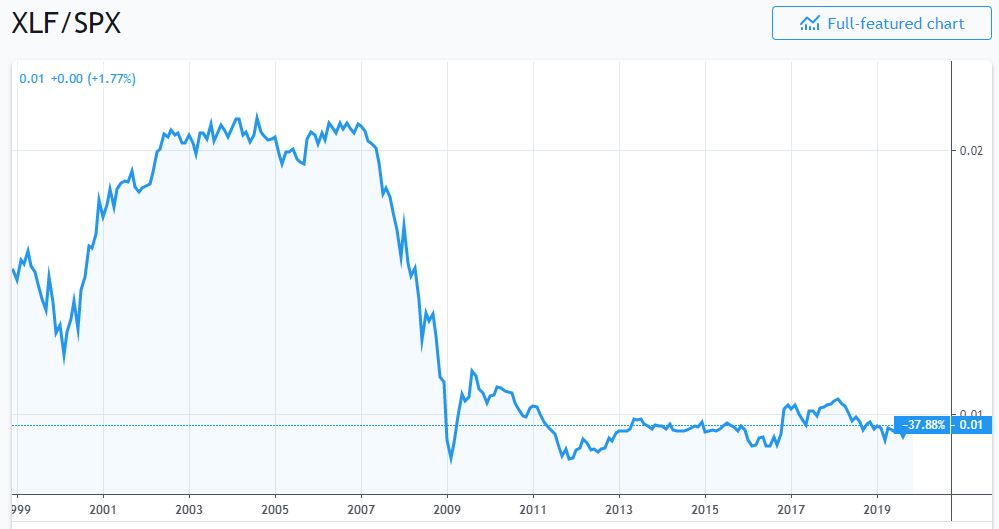

The more medium outlook really has to do with whether the specialness of US equities will persist and whether the passive investing trend will continue. Despite, in fact, perhaps because of the selloff last week, market commentators have continued to reinforce the idea of the futility of trying to time market gyrations and the superiority of staying always invested (there are too many examples, but see here, here, and here). This all makes sense and we have the data historically, on a long enough time frame, to prove it. However, this holds mostly for US stocks which have outperformed all other major stocks markets around the world. And that is despite lower (and negative) rates in Europe and Japan where, in addition, CBs have also been buying corporate assets direct (bonds by ECB, bonds and equities by BOJ).

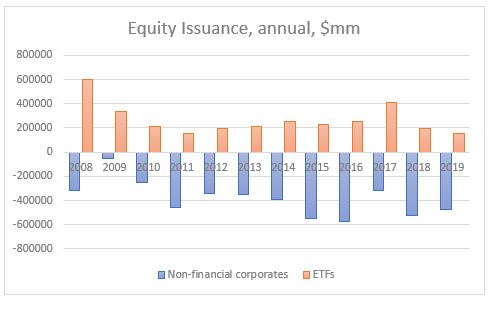

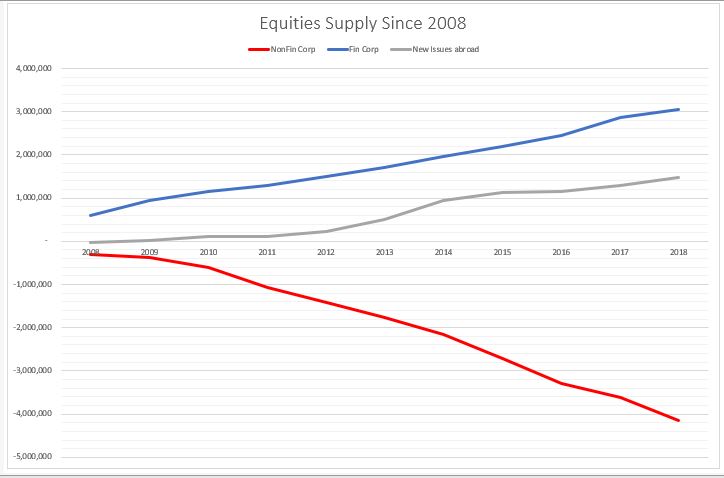

Which begs the question what makes US stocks so special? Is it the preeminent position the US holds in the world as a whole? The largest economy in the world? The most innovative companies? The shareholders’ primacy doctrine and the share buybacks which it enshrines? One of the lowest corporate tax rates for the largest market cap companies, net of tax havens?…

I don’t know what is the exact reason for this occurrence but in the spirit of ‘past performance is not guarantee for future success’s it is prudent when we invest to keep in mind that there are a lot of shifting sands at the moment which may invalidate any of the reasons cited above: from China’s advance in both economic size, geopolitical (and military) importance, and technological prowess (5G, digitalization) to potential regulatory changes (started with banking – Basel, possibly moving to technology – monopoly, data ownership, privacy, market access – share buybacks, and taxation – larger US government budgets bring corporate tax havens into the focus).

The same holds true for the passive investing trend. History (again, in the US mostly) is on its side in terms of superiority of returns. Low volatility and low rates, have been an essential part of reinforcing this trend. Will the CV and US probably inadequate response to it change that? For the moment, the market still believes in V-shaped recoveries because even the dotcom bust and the 2008 financial crisis, to a certain extent, have been such. But markets don’t always go up. In the past it had taken decades for even the US stock market to better its previous peaks. In other countries, like Japan, for example, the stock market is still below its previous set in 1990.

While the Fed has indeed said it stands ready to lower rates if the situation with the CV deteriorates, it is not certain how central bankers will respond if an unexpected burst of inflation comes about on the back of the supply shock (and if the 1980s is any sign, not too well indeed). Even without a spike in US interest rates, a 20-30 VIX investing environment, instead of the prevailing 10-20 for most of the post 2009 period, brought about by pulling some of the foundational reasons for the specialness of US equities out, may cause a rethink of the passive trend.