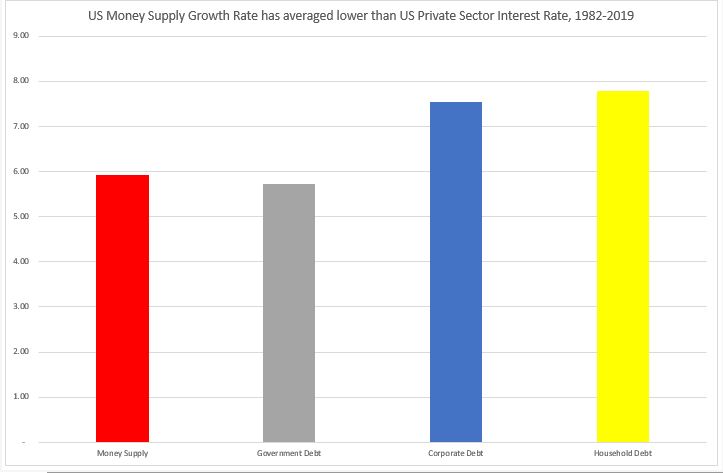

In the current debt-backed system, the majority of money is still loaned into circulation at a positive interest rate. Even in Europe and Japan, where base interest rates and sovereign bond yields are negative, the majority of private debt still carries a positive interest rate. This structure inherently requires a constantly growing portion of the existing stock of money to be devoted to paying solely interest. Thus, the rate of growth of the money supply has to be equal to or greater than the rate of interest, otherwise more and more money would be devoted to paying interest than to economic activity.

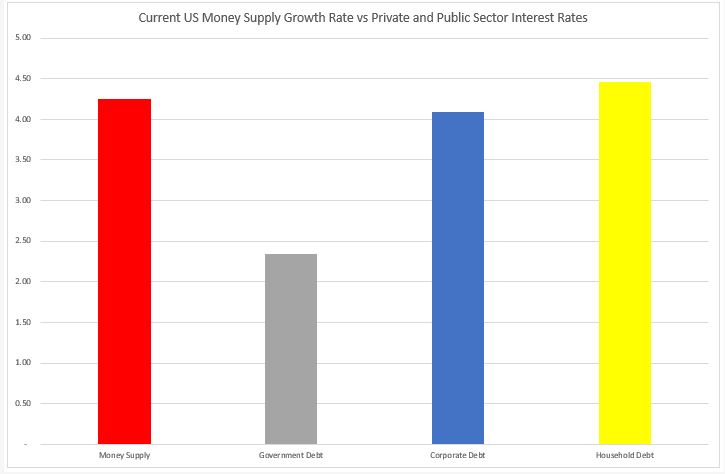

The long-term average growth rate of US money supply is around 6%, which is only slightly higher than the average interest rate on US government debt but it is below both the average US corporate interest rate and US household debt. While I have used the UST 10yr yield as the average yield on US government debt (the average maturity of US debt is slightly less than that), the estimates for both US corporate debt and US household debt are very generous. For the former, I used the average yield on Aaa and Baa corporate bonds, and for the latter I used a weighted average interest rate between mortgage debt and auto loans (I have used 2/3 and 1/3 weights). I have not included the much higher yield on US corporate junk bonds which comprise a growing proportion of overall corporate debt. I have also not used credit card/consumer debt, which has a much higher interest rate than auto loans, and also student loan debt which carries approximately similar interest rate to auto loans. Just like for BBB and lower rated US corporates, credit card and student loan debt are a much higher proportion of total US household indebtedness compared to before the 2008 crisis.

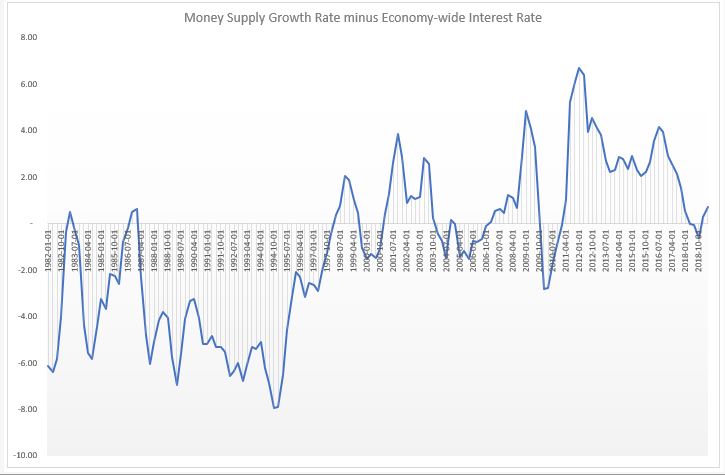

I estimate the long-term average economy-wide interest rate as a weighted average of government, corporate and household debt – with the weights being their portions of the total stock of debt. That rate currently is about 7%, still higher than the average money supply growth rate since the early 1980s. Over the last four decades, US money supply has not only not grown enough, on average, to stimulate US economic growth, but has been, in fact even, below the overall interest rate in the economy. Needless to say, this is not an environment that could have persisted for a long time.

Indeed, if one calculates the above equivalent rates for the period 1980-2007, the situation would be even more extreme (see Chart below). In fact, until the late 1990s, money supply growth had been pretty much consistently below the economy-wide interest rate. Only after the dotcom crisis, but really after the 2008 crisis, money supply growth rate picked up and stayed on average above the economy-wide interest rate.

What is the situation now? The current money supply growth rate is just above the average economy-wide interest rate; respectively above the government and corporate interest rates but below the household interest rate (data is as of Q1’2019).

It is also still below the combined average private sector interest rate.

So, even at these low interest rate, US money supply is just about enough to cover interest payments on previously created money. And that is assuming equal distribution of money. Reality is that it is only enough to cover interest payment on public debt. And even in the private sector, money distribution is very skewed: corporates have record amount of cash but it is only in the treasuries of few corporates. The private sector, overall, can barely cover its interest payment, let alone invest in CAPEX, etc.

The deeper question is whether money creation should indeed be linked to debt at positive interest rate. In fact, we have already answered that question, and gone beyond, with some portion of money creation in Europe and Japan actually happening at negative interest rate. In effect, the market is trying to correct for all those decades when money creation substantially lagged interest payments: money there is starting to decay.

Demurrage money is not unusual in history. Early forms of commodity money, like grain and cattle, was indeed subject to decay. Even metallic money, later, on was subject to inherent ‘negative interest rates’. In the Middle Ages, in Europe, coins were periodically recoiled and then re-minted at a discount rate (in England, for example, this was done every 6 years, and for every four coins, only three were issued back). Money supply though, did not shrink, as the authorities (the king) would replenish the difference to find his own expenses. In 1906, Silvio Gesell proposed a system of demurrage money which he called Freigeld (free money), effectively placing a stamp on each paper note costing a fraction of the note’s value over a specific time period. During the Great Depression, Gesell’s idea was used in some parts of Europe (the wara and the Worgl) with the demurrage rate of 1% per month.

The idea behind demurrage money is to decouple two of the three attributes of money: store of value vs medium of exchange. These two cannot possibly co-exist and are in constant ‘conflict’ with each other: a medium of exchange needs to circulate to have any value, but a store of value, by default, ‘requires’ money to be kept out of circulation. Negative interest rates in effect split these two functions.

Seen from this point of view, negative interest rates may not be a temporary phenomenon just to spur lending. On the opposite, negative interest rates may be here to help reduce the overall debt stock in the economy and to escape the deflationary liquidity trap caused by the declining marginal efficiency of capital.