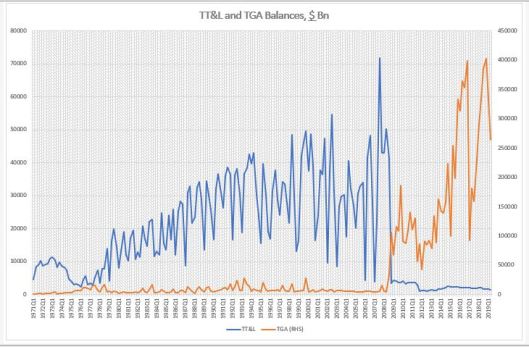

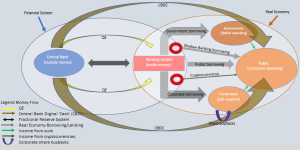

At present, majority of money (medium of exchange=inside money) creation in the developed world gets done by private banks. The state (government and/or the central bank =outside money) does create money but it is either as a medium of exchange within the banking system only, or on the back of demand for physical cash in exchange for inside money.

I have written about this before here (‘A simplified hierarchy of money’). The problem with the current monetary transmission mechanism (‘A simplified version of the monetary transmission mechanism’) is that it is set up almost by default to produce a scarcity of money. One alternative could be that the central bank distributes money directly using all the available data management techniques and recent advances of technology (central bank digital cash).

Given the state of our economy, and in order to properly address the level of technological advances we are experiencing, i.e. to minimize the risk of disruptions which could lead to social upheavals and loss of our prosperity, it could be a good idea to look at history to see how money was created and distributed in similar periods of development.

(Click to enlarge)

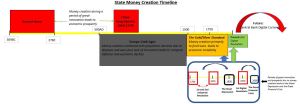

Indeed, inside vs. outside money creation is only a recent phenomenon (late 20th century) while state money creation had been the norm for the majority of human existence. And that’s the thing. Unfortunately, our current views of state money creation are really shaped by the most recent examples which had been disasters. For example, the Gold Standard came into existence to curb the rampant money creation to fund wars during the European Dark Age. In addition, that was a period without any major commercial innovations and characterized by population stagnation across Europe.

The late 18th and the 19th century, on the other hand, saw the 1st and 2nd Industrial Revolution which introduced new modes of production. The second half of the 19th century up to early 20th century was also characterized by a period of general peace (Pax Britannica). By then the great innovations of the previous two centuries were also commercialized. As a result of all this, Europe, in particular, became very prosperous.

Unfortunately, the existence of the Gold Standard, prohibited the state to issue enough money to correspond to the increased potential of economic activity. The Great Depression in the 1930s was thus characterized by a positive supply shock, on the back of these innovations, and a negative demand shock on the back of insufficient supply of the medium of exchange.

Early 20th century was probably the first time humanity was experiencing the fruits of progress on a basis similar in scale to the period of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) in China and the Roman Republic (509BC-27BC). Yet, policy makers failed to take full advantage of this by unnecessarily restricting the flow of money. It took a global war which destroyed/redirected a large part of Europe’s industrial capacity to re-address the imbalance between supply and demand.

Even then, policy makers, still did not take note that there was a paradigm shift in the late 1800s after the 1st Industrial Revolution, when a period of innovations massively shifted our economic potential much higher. While the developed world was slowly moving away from ‘scarcity’ and closer to ‘abundance’, they continued to operate from the basis that supply of resources is the bigger issue. The period from the end of the WW2 to the early 1970s continued to be characterized by a restrictive flow of money, the quasi gold standard. Luckily, it did take some time for capacity to come back on line after the war, so there were no major financial disasters.

In fact, it was quite ironical, that as soon as President Nixon decided to finally fully abandon the gold standard and introduce the age of fiat money, the world experienced a supply side crisis: due to problems in the Middle East, the supply of oil became restricted leading to a rise in inflation. This actually emboldened policy makers even further to focus on issues emanating from insufficient supply of resources and thus manage the demand side of the economy more closely to reflect that. The problem on the supply side, however, was short-lived, and as soon as the Middle East crisis subsided, oil started flowing back and ‘equilibrium’ ensued.

Nevertheless, even to the present day, our economic policy is still dictated by the mantra of supply side economics and inflation targeting.

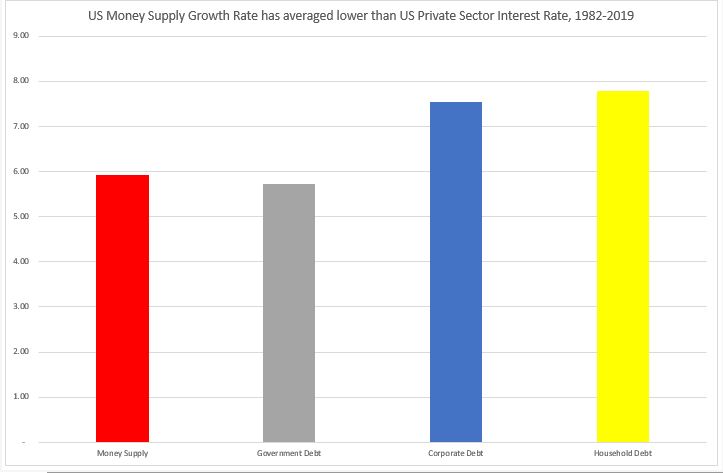

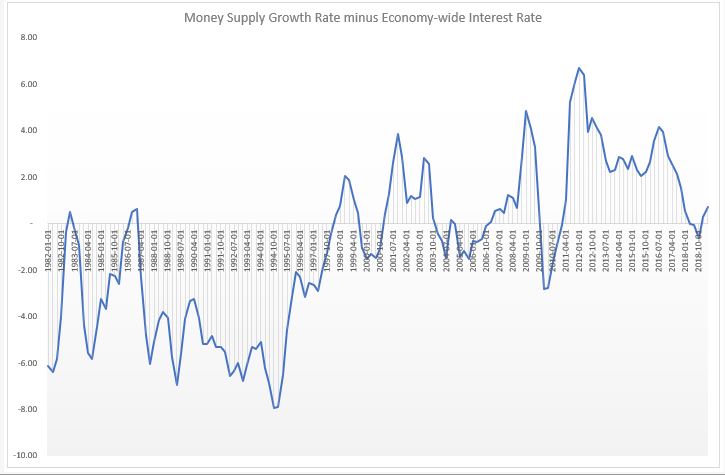

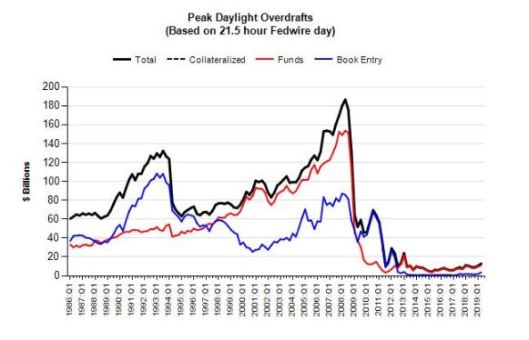

Alongside these developments, the second half of the 20th century was also characterized by the start of the 1st Digital Revolution with the invention of the computer in the 1950s and its commercialization in the 1980s. Starting in the 1990s, globalization also took off. These developments boosted even further potential supply, while at the same time, money flow, despite no restrictions on actual money supply due to its fiat nature (but actual restrictions due to the separation of outside and inside money) continued to be restrictive.

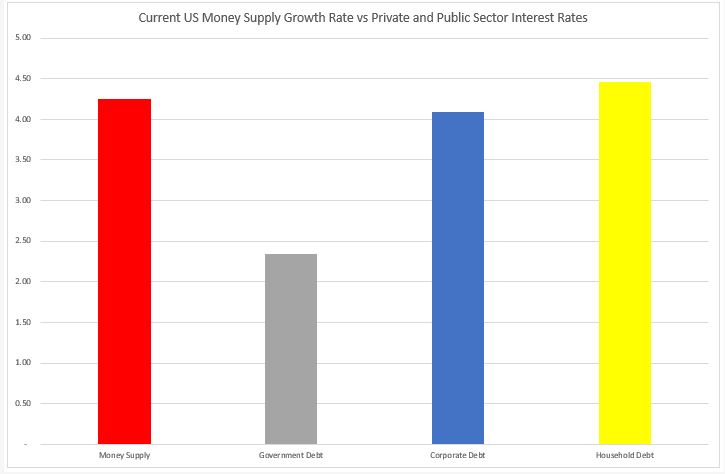

These were the developments which led to the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, which, just like the Great Depression before, was characterized by a positive supply shock due to a burst of the commercialization of previous innovations and a negative demand shock due to insufficient money supply. The present time seems also to be the beginning of what could be called the 2nd Digital Revolution of AI and VR, which has the potential to even further increase our economic potential. Yet, when it comes to money creation, we are still operating with the mentality the Gold Standard: money is kept excessively restricted for fear of rising inflation.

In light of this, it could be worthwhile to point out that there were actually periods of successful state money creation in the past: Rome in the last five centuries BC and China between 10th and 13th century. Why did state money creation work back then? Three main reasons:

- massive prosperity on the back of the commercialization of previous innovations,

- a period of relative peace, and

- a properly working institutional framework

It is important also to note that both in the beginning of the 20th century and now, all these three reasons above are present. If history is any guide, failure to supply the necessary amount of medium of exchange to ‘record’ this existing prosperity could lead to war, followed by disappearance of the economic prosperity, and in the worst possible scenario (did not happen during the Great Depression) the dismantling of the institutional framework. Or, if more recent political developments are any guide, could this time be different and the decline starts with the dismantling of the institutional framework, followed by war and the natural disappearance of prosperity?

To sum up:

- state money creation is good when it is done within a solid institutional framework, and it follows (or is accompanied) by a positive supply shock brought about by previous innovations leading to economic prosperity (past examples: the Roman Republic, China during the Song Dynasty; no current examples);

- state money creation leads to negative outcomes when it follows a negative supply shock brought about by war, natural population declines, or inadequate institutional framework (Europe during the Dark Age, the Gold Standard; more recent examples: Zimbabwe, Turkey, Argentina, etc.)