What determines interest rates and how lower private sector profitability, changes in the institutional infrastructure governing our economies, major geopolitical conflicts, and climate change, could usher in a ‘sea change’ of higher interest rates[i].

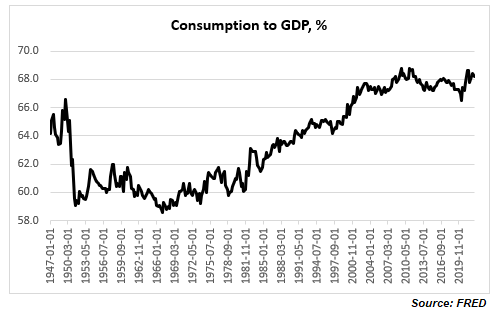

The simplest possible explanation of what drives interest rates is the demand and supply of capital and its mirror image debt. I find this to be also the most relevant one.

There are many other variables that matter, which fall under the broad umbrella of economic activity. These factors determine the ability to pay/probability of default and may impose a certain ‘hurdle rate’ (inflation), but it is important to understand that they are a consideration of mostly the supply side of capital.

So, what is a ‘normal’ interest rate? Obviously, when capital is ‘scarce’ (relative to the demand for debt), as indeed for the majority of time of human existence and ‘capital markets’, creditors are ‘in charge’, nominal interest are high and real interest rates are positive. So, that is the norm. But in times of peace and prosperity, as during the time of Pax Britannica (most of the 19th century), and Pax Americana (since the 1980s, and particularly since the end of the Cold war) surplus capital accumulates which gradually pushes interest rates lower as the debtors are ‘in charge’. The norm then could be zero and even negative nominal interest rates.

While indeed the norm is for interest rates to be positive, there is no denying that if one were to fit a trend line of global interest rates in the last 5,000 years[ii], the line would be downward sloping. That should be highly intuitive as human society evolution brings longer lasting periods of peace and prosperity (the spikes higher in interest rates throughout the ages are characterised with times of calamities, like wars or natural disasters, which destroy capital).

What is the function which determines that outcome? The surplus capital inevitably creates a huge amount of debt. This stock of debt eventually rises to a point which makes the addition of more debt an ‘impossibility’. It is important to understand that this happens on the demand side, not on the supply side – it is current debt holders who find it prohibitive to add to their current stock of debt, in some cases, at any positive interest rates.

Richard Koo called this phenomenon a balance sheet recession when he analysed the behaviour of the private corporate sector in Japan after the 1990s collapse. We further saw this after the mortgage crisis in the US in 2008 when US households started deleveraging. Not surprisingly interest rates during that time gravitated towards 0%.

The importance of 0% and particularly negative interest rates is not only that this is where the demand of debt and supply of capital clears, but, more importantly from a ‘fundamental’ point of view, this is the point where the current stock of debt either stops growing (0%) or even starts to decrease (negative interest rates). Positive interest rates, ceteris paribus, on the other hand, have an almost in-built automated function which increases the stock of debt (in the case of refinancing, which happens all the time – rarely is debt repaid).

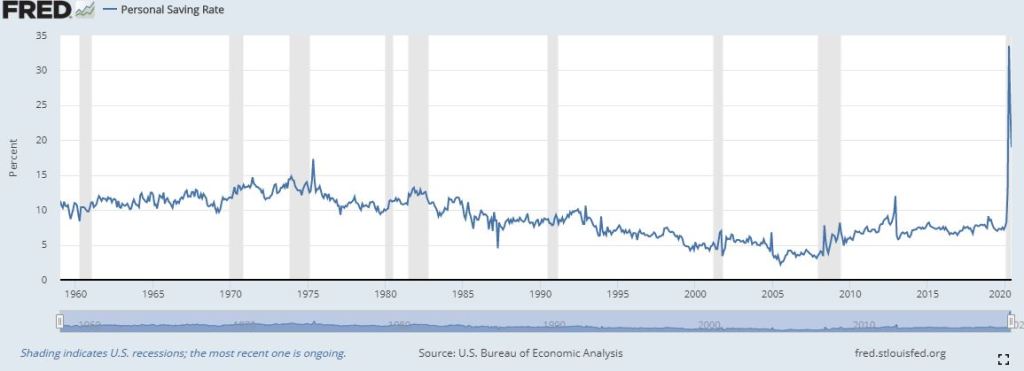

Because our monetary system is credit based, i.e., money creation is a function of debt origination and intermediation, this balance sheet recession, when the demand for credit from the private sector is low or non-existent, naturally pushes down economic activity, which, ceteris paribus, results in a low, and sometimes negative, rate of inflation.

So, you see, it is low interest rates which, in this case, determine the inflation rate. This comes against all mainstream economic thinking. I am sure, a lot of people, would find this crazy, moreover, because this is also what Turkish President Erdogan has claimed, and it is plain to see that he is ‘wrong’.

However, there is a reason ‘wrong’ above is in quotation marks. You see, this theory of low interest rates determining the rate of inflation, and not the other way around, holds under two very important conditions. First, and I already mentioned this, the monetary mechanism must be credit-based. This ensures that money creation is not interfered by an arbitrary centrally governed institution, like … the government, and is market-based, i.e., there is no excess money creation over and above economic activity.

In light of a long history of money waste, this sounds like a very reasonable set-up, except in the extreme cases when the stock of debt eventually piles up, pushing down the demand for more credit, slowing down money creation and thus economic activity. In times like these, it is the rate of money creation which determines and guides economic activity rather than the other way around (as it should be). Unless there is an artificial mechanism of debt reduction, like a debt jubilee, the market finds its own solution of zero or negative interest rates to resolve the issue.

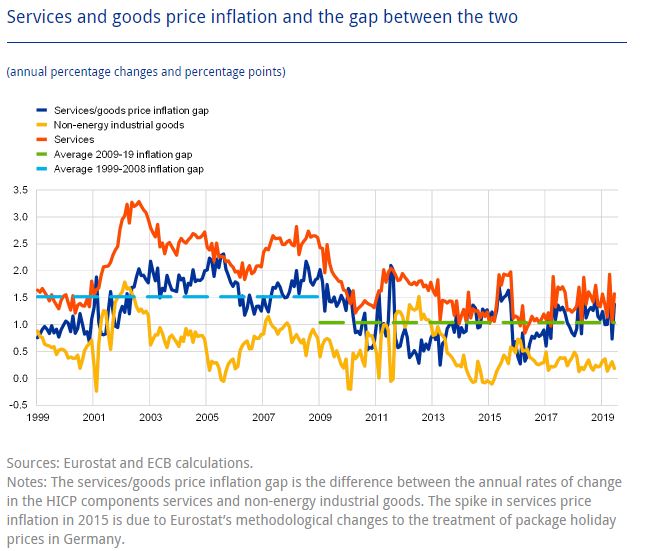

And the second condition for the above theory to hold is the supply side of the economy must be stable. Don’t forget that inflation is also independently determined by what happens on the supply side: a sudden negative supply shock would push inflation higher. That the balance sheet recessions in Japan, and later on in the rest of the developed world, coincided with a positive supply shock accentuated its disinflationary impact.

To go back to Turkey, Erdogan’s monetary experiment is not working because 1) Turkey’s economy is not in a balance sheet recession (private sector debt is not big, and there is plenty of demand for credit), and 2) Turkey’s economy was hit by a large negative supply shock in the aftermath of the breakdown of global supply chains on the back of Covid/China tariffs, and, more particularly for Turkey being a large energy importer, in the aftermath of the Russian sanctions on global oil prices. A related third reason why low interest rates in Turkey have failed to push inflation lower is the fact that institutional trust is low. In other words, the low interest rates are not market-based, but government-based (market-based interest rates are in fact much higher).

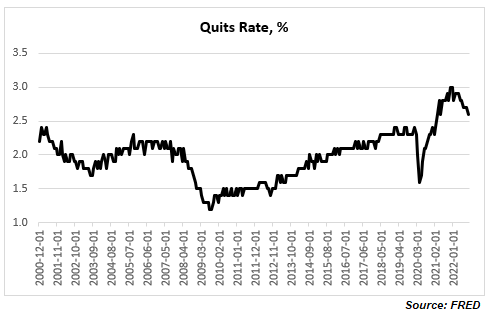

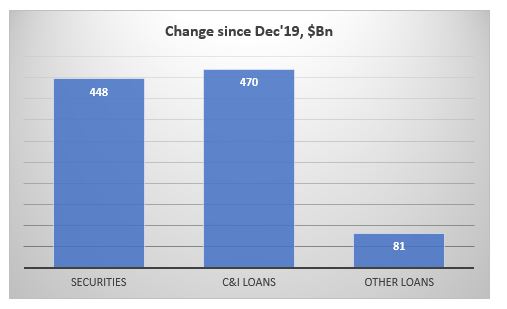

What has happened in the developed world, on the other hand, is, since Covid not only the economies have experienced a massive negative supply shock, but also monetary creation, for a while (well, most of 2020-21) became central-government-based (in the form of huge household transfers). In other words, even though private debt levels remain excessive, their negative effect on economic activity has been offset by other forms of money creation. This not only managed to reverse the disinflationary trend from before, but, when combined with the negative supply shock, it provoked a powerful inflationary trend.

Going forward, unless there is a repeat of the central-government-based money creation experiment under Covid, the demand for credit, and thus the growth of money creation, will remain low, as private sector debt levels remain too high. This does not bide well for economic growth and is disinflationary by default. At the same time, however, the effects of the negative supply shock are likely to be longer lasting given that the reorganization of the global supply chains is still an ongoing process. This is inflationary by default – if that means also lower private sector profits, thus lower capital surpluses, then interest rates should continue to be elevated.

When it comes to the developed world the black swan here is an eventual outright debt reduction (debt jubilee) – the will have a corresponding effect of an artificial capital surplus reduction as well. Maybe this is counterintuitive, but if you have followed my reasoning up to here, that would mean higher interest rates going forward.

An alternative black swan is a direct capital surplus reduction, caused by either lower corporate profitability, lower asset prices, or indeed an artificial or natural calamity, like war or a natural disaster, which have the unfortunate ability to destroy capital. In that sense, it is uncanny that our present circumstances are characterised by a war in Europe, a potential war in Asia and the looming threat of climate change[iii].

Howard Marks certainly did not mean literal ‘sea change’ in his latest missive, but this might ironically be one of the main determinants of higher interest rates in the future.

For more on this topic you might also find these posts interesting:

It would take a ‘revolution’ to wipe out negative rates

Negative interest rates may not be a temporary measure

Inflation in the 21st century is a supply-side phenomenon

‘State’ money creation – this ghost from the past is badly needed for the future

[i] This post was inspired by Howard Mark’s latest, Sea Change, and, more particularly, by his interview on the subject.

[ii] https://www.businessinsider.com/interest-rates-5000-year-history-2017-9?r=US&IR=T

[iii] We live by the sea, literally. When we bought the house in 2007, the sea was about 100 meters from the fence of our garden, in normal times. This has now been reduced at least by half. In the last three years, the sea has often come into our garden, which has prompted us to spend money on reinforcing the fence etc., which has naturally reduced our capital surplus.